Long-tall Adam

/Last weekend's Sunday Times STYLE magazine featured a section called 'Those Warm Wild Nights' in which eight critically acclaimed writers shared unforgettable summer encounters. I enjoyed the read a lot, and of course it got me thinking about what I would have written if they had asked me, so I got up from the breakfast table and wrote my own.

Long-tall Adam

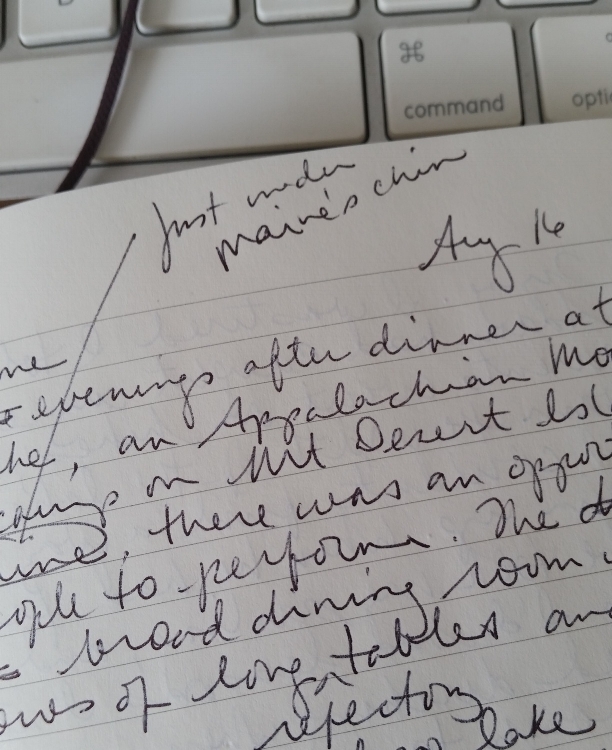

On some evenings after dinner at Echo Lake, an Appalachian Mountain Club camp on Mt Desert Island, just under Maine’s chin, there was an opportunity for guests to perform. The broad dining room with its rows of long refectory tables and views of the mile-long lake had an upright piano. My dad was a jazz pianist, and this meant he met long-tall Adam before I did. Adam, one of the crew at work there for the summer, played the fiddle. The only entertainment I can remember from the evening they played together in the summer of 1982, when I was 16, is their rendition of ‘Satin Doll’.

My mother had imagined much family fun on that trip to Maine, I’m sure. The camp organized daily hikes and climbs, but I refused them all. I had hiked 40 miles of the Long Trail in Vermont already that summer (also her idea), and had starred as Rosemary in our town’s production of How to Succeed in Business Without Really Trying. I was tired, I told her. But Adam had caught my eye.

My parents went on hikes, and I swam the width of the lake, watched by loons, when I couldn’t find a way to chat Adam up. When he had free time he took me sailing. Although I’d had lessons I still mistimed ducking under the boom when we swung around often enough to have angry grazes on my shoulder when we returned to shore. It raised some eyebrows. Another crew member joked, ‘What’s he been doing to you out there?’ I joked back, ‘You should have seen what he wanted me to do.’ He and Adam both laughed. They looked impressed. I felt cool. That was what I did those days. I talked plenty sexy. But I avoided the act for another five years.

My parents agreed to allow Adam to take me out in a rowboat under the crowded stars on our last night at the lake. I remember sitting on his long lap, embraced by his atmosphere of liberal intellect and coffee, my neck tickled by his soft goatee, telling him I wished my parents were dead. (So sue me. I was 16.) We were out there a long time, and when we got back to the camp and walked up to the deck where we would part, my mother was standing there waiting, livid, in a knee-length, nylon, leopard-print nightgown.

I now know that parents have internal clocks set for when their children should be home, even if they haven’t expressed that time as a number. They – we – just feel it: the reasonable amount of time for such an excursion has passed, and my daughter should be back by now. Having been allowed to go out without a curfew, I couldn’t understand her anger that night. I imagined her trying to get my father to do the confronting, imagined her frustration when he quite rightly didn’t feel as strongly as she did, imagined her storming out of the tent. The embarrassment was acute. But now the memory of watching her lay into Adam in the moonlight, her head tipped back to look up at his bowed head, his abashed face, is an emblem for me now. I’m no longer embarrassed by it; I’m impressed, because I’m no longer a beleaguered teenager. I’m a mother. I know the fangs and claws we grow when protective. So on that starry summer night, I went out in a rowboat with a man, but she was the wild one.